Building Technology

The technology of house construction at the Neolithic settlement of Avgi

The study of building technology through the analysis of domestic architectural remains contributes greatly into the understanding of human activity during the Neolithic period. The neolithic house has been commonly approached as the centre of production, consumption and redistribution, as well as a fundamental unit of spatial organisation with multiple social and symbolic dimensions. What is more, archaeological research during the last decades has shown that domestic structures should also be viewed as ‘artefacts’ or technological products subjected to similar conceptual schemes as other artefact categories (Shaffer 1983; Stevanović 2006; 2007). The application of a technological approach, rather than being restricted to the purely material aspects of buildings (including built forms, ground plans, building materials etc) or the broad limiting factors that influence their final form (such as the environment, the climate and the availability of resources), also focuses on the multifaceted aspects of the construction practices that formulate them. Besides, the house construction process as a whole constitutes an integral part of human activity that is embedded in social relations and is highly influenced by cultural traditions and social imaginaries (Rapoport 1969; Olivier 2003).

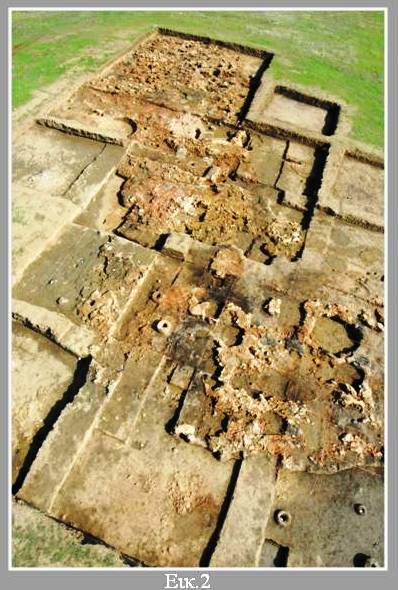

Figs. 1 & 2

The main sources of information for the building activity at the Neolithic settlement of Avgi derive a) from the negative impressions of structures, such as post- or stake-holes, foundation pits and trenches, and b) from the considerable number of daub fragments that belong to successive wall plasters or bear multiple impressions of the timber frame. The latter finds (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) can be associated with different parts of the superstructure that were ceramified during the destruction of buildings by fire. Their impressive status of preservation, especially of those belonging to the second half of the 6th millennium (phase AVGI I), offers the possibility of a detailed analysis of the construction techniques and the skills employed. The study of the building remains of the site comprises part of the author’s ongoing PhD research at the

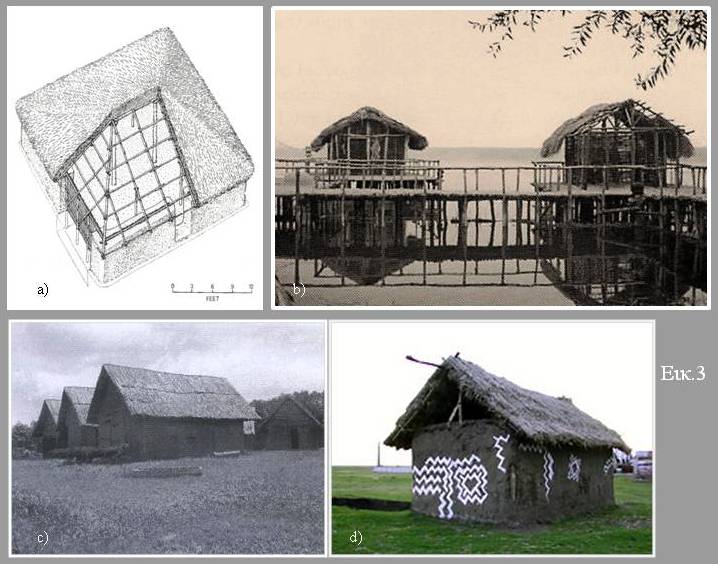

Fig. 3

The preliminary study of the material suggests that the building technology of Avgi finds parallels in the architectural tradition of northern

The main building materials include timber, mud or clayish earth, water for the mixing of clay, reeds and other plant resources for tempering or for the construction of roofs. On the contrary, the use of stone for the construction of footings or foundation reinforcements (Mylonas 1929; Mould & Wardle 2000) is not documented in any of the settlement’s dwellings. It seems reasonable that the heavy and bulky resources were, more or less, easily accessible by Neolithic inhabitants. The study of the palaeoenvironment supports the existence of water sources in the vicinity of the settlement, as well as the availability of appropriate timber sources in the surrounding woodlands (see Ntinou 2008). Clayish earth is commonly considered as local, quarried from nearby sources. In the case of Avgi and other Neolithic sites of northern Greece, such as Nea Nikomedeia and Makriyalos (Pyke 1996, 49; Pappa & Besios 1999, 182) this assertion is reinforced by the suitability of local deposits, as well as by the excavation of numerous pits in the settlements’ area or their periphery. Some of them could have been initially constructed for the procurement of clay and later could have been used as rubbish pits. Besides, this was a common practice in SE Europe until recently (

After the assembling of building materials, foundations were dug for the erection of the major posts (probably made of oak, pine or other coniferous trees) and the roofs. In the case of the earlier building horizon, it is probable that foundations consisted of sizeable posts or rows of posts sunk directly into the soil. However, the scarcity of post-holes that can be stratigraphically associated with the AVGI I dwellings renders problematic the identification of the exact foundation techniques. Concerning the later phase of habitation (AVGI III), the available excavation data are more informative. Foundation techniques include deep, U-shaped foundation trenches that reach 0.50m in width. The posts of the timber frame are sunk inside these trenches in various configurations (single or double rows of densely or more sparsely arranged posts – Στρατούλη 2005; 2010, 11). What is more, the excavation of large post-holes or foundation pits inside Building 2b indicate that internal buttresses or central posts were sometimes added to offer extra support for the roof (Στρατούλη & Μπεκιάρης 2011). The significance of the changes in the foundation techniques cannot be easily interpreted. If the durability of dwellings is put forth as a possible reason of the later development, the use of foundation trenches and pits could reflect the construction of more sizeable buildings during the later phase of habitation.

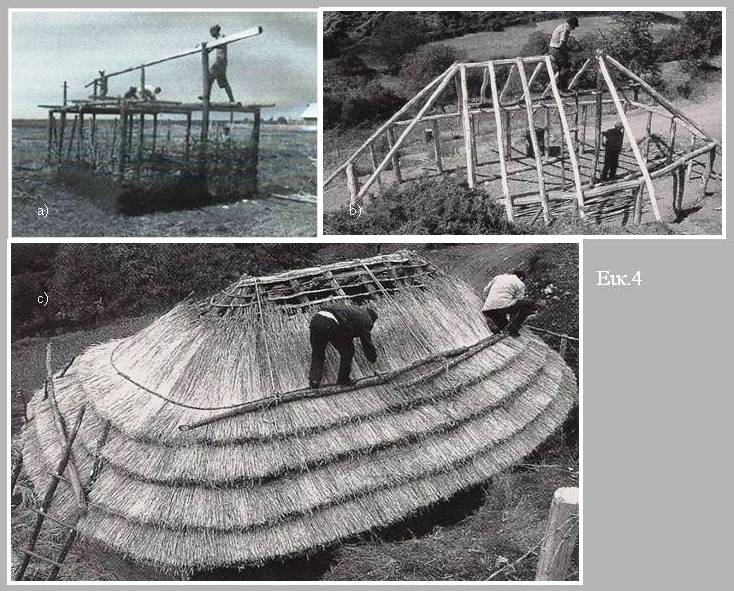

Figs. 4 & 5

The roofs of Neolithic dwellings are commonly thought to be pitched with wooden rafters covered either with mud-plastered reeds or with un-plastered thatch (Fig. 4). Their reconstruction is, by and large, based on clay house models and ethnographic parallels. Occasionally, such assumptions are reinforced by the impressions of reeds or straw on daub fragments from sites in northern

Moving to the construction of the wall frame, more reliable information can be drawn. The study of the architectural remains of Building 5 and other structures of the earliest building horizon indicates the application of alternative techniques. One of the most common walling techniques consists of closely set stakes and split timbers (Fig. 5). The diameter of cylindrical stakes, ranging from 0.06 to

Figs. 6 & 7

Parallel to the use of closely set timbers, a considerable number of daub fragments confirm the employment of the wattle-and-daub technique that is the weaving of long pliant branches or reeds between uprights (Fig. 6). This technique, although frequently considered as the most common in the region of northern

Considering the technological skills and choices of the Neolithic inhabitants, the use of thin planks (approximately 2-

Fig. 8

After being set, the timber frame was packed with mud or clayish earth that was probably applied by throwing and then smoothened by hand. The mixture usually contained vegetable tempers such as chopped straw or chaff (Fig. 8). Other inclusions that are macroscopically visible include pottery sherds, pebbles, shells etc. However, it is highly probable that these were incidental inclusions, associated with deliberate or non deliberate choices in the quarrying and processing of clay. Whatever the case may be, the ceramified daub fragments of the superstructure indicate the application of successive layers of daub and thin finishing plasters, thus supporting the periodical renewal or repairing of the wall surfaces.

Concerning the floors of the AVGI I buildings, two different construction techniques are shown. The first technique includes the plastering of house floors or specific parts of floors with a clayish mixture, while the second one was the technique commonly described as trampled earth. In contrast to other sites in the region of northern

In summarising the available evidence, it becomes clear that the material under study has already offered some useful insights into the building technology of Neolithic Avgi, especially during the late 6th millennium. As already noted, the building remains of the site reflect a multifaceted chaîne opératoire. Beside the main building techniques reported so far, a number of finds indicate the application of a wide range of variations (e.g. the use of planks or branches that are set in parallel rows without being weaved) or alternative methods of construction (including the pisé technique). It is obvious that some of these techniques (e.g. wattle-and-daub and pisé) co-exist in the same building. Moreover, traces of both homogeneity and diversity are observable (e.g. foundation techniques, wall construction and floors) not only when comparing structures that belong to different phases but also between structures of the same building horizon.

The identification and interpretation of variability in the different stages and ramifications of the chaîne opératoire is one of the main objectives of future research. In this attempt, the tacking between different scales of analysis (e.g. dwelling, house cluster, settlement, region) and the refinement of the terminology applied seems crucial, lest evidence of intra- or inter-site differentiation is overlooked. As it is the case with other categories of the material culture, house construction does not necessarily follow strict rules or widely accepted prescriptions. Rather than being essentially static and conservative, it should be approached as a dynamic part of human action that is potentially subjected to constant renegotiation. The detailed analysis of well preserved remains, such as those of Avgi and other sites, may shed light on relevant issues.

List of figures

Fig. 1. Rubble of Building 5 (Avgi I) at the western sector of the site (Archive of the excavations at the Neolithic settlement of Avgi, Kastoria, photo: G. Vlachos).

Fig. 2. Rubble of buildings 1 and 7 (Avgi I) at the eastern sector of the site (Archive of the Excavations at the Neolithic settlement of Avgi, photo: G. Vlachos).

Fig. 3. Graphical and experimental reconstructions of Neolithic houses in northern Greece and the Balkans: a) Nea Nikomedeia (Rodden 1965, p. 87), b) Dispilio open-air museum (Αλματζή 2002, p. 28), c) Sopot, Croatia (Balen 2010, fig. 6.3, p.58), d) Vadastra, Romania (Gheorgiu 2004, fig. 1).

Fig. 4. The construction of the roof: a) experimental reconstruction of a prehistoric house at the Vadastra region in Romania (Gheorgiu 2010, fig. 11.7, p. 98, b, c) traditional hut at the Sarakini settlement in Rhodope (Ευστρατίου 2002, fig. 99, p. 388, fig. 108, p. 392).

Fig. 5. Daub fragments with impressions of closely set stakes (photo: D. Kloukinas).

Fig. 6. Daub fragments with impressions of split timber or ‘planks’ (photo D. Kloukinas).

Fig. 7. Daub fragments with impressions of intertwined wattles (photo: D. Kloukinas).

Fig. 8. The preparation of the construction earth and the plastering of the timber frame: a, b) traditional hut at the Sarakini settlement in Rhodope (Ευστρατίου 2002, fig. 110 & 111, p. 393, c) experimental reconstruction of a Neolithic house wall at the Neolithic settlement of Dikili Tash, Drama (Martinez 1999, fig. 9, p. 48).

Bibliography

Αλματζή, Α. 2002. Γενικά για τους πολιτισμούς του νερού. In Γ.Χ. Χουρμουζιάδης (ed.), Δισπηλιό 7500 χρόνια μετά, 25–35. Θεσσαλονίκη: University Studio Press.

Balen, J. 2010. Building techniques during the Neolithic and Eneolithic in

Buttler, W. 1936. Pits and pit-dwellings in

Ευστρατίου, Ν. 2002. Εθνοαρχαιολογικές αναζητήσεις στα Πομακοχώρια της Ροδόπης.

Gheorghiu, D. 2004. Project Vadastra: 2004 pictures. In http://www.pcrg.org.uk/Articles/vadastra_page.htm

Gheorghiu, D. 2010. The technology of building in Chalcolithic Southeastern Europe. In D. Gheorghiu (ed.), Neolithic and Chalcolithic archaeology in

Kloukinas, D. (in progress). Neolithic building technology and the social context of construction practices: the case of Neolithic northern

Lichter, C. 2003. Untersuchungen zu den Bauten des sudeuropäischen Neolithikums und Chalkolithikums. Erlbach: Verlag Marie L. Leidorf.

McPherron, A. & Srejović, D. (eds.). 1988. Divostin and the Neolithic of

Mylonas, G. E. 1929. Excavations at

Nτίνου, Μ. 2008. Η εφαρμογή της ανθρακολογίας στο νεολιθικό οικισμό της Αυγής. In http://www.neolithicavgi.gr/?page_id=116&langswitch_lang=el.

Olivier, P. 2003. Dwellings: the vernacular house worldwide.

Pappa, M. & Besios, M. 1999. Makriyalos,

Pyke, G .1996. Structures and architecture. In R.J. Rodden and A.K. Wardle (eds.), Nea Nikomedeia I. The Excavation of an Early Neolithic Village in

Rapoport, A. 1969. House form and culture.

Rodden, R.J. 1965. An Early Neolithic village in

Shaffer, M.D. 1983. Neolithic building technology in

Stevanović, M. 1996. The age of clay: the social dynamics of house destruction. Unpublished PhD dissertation. UC Berkeley.

Stevanović, M. 1997. The age of clay: the social dynamics of house destruction. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 16, 334-95.

Στρατούλη, Γ. 2005. Μεταξύ πηλών, πλίνθων και πασσάλων, μαγνητικών σημάτων και αρχαιολογικών ερωτημάτων: τάφροι οριοθέτησης και θεμελίωσης στον νεολιθικό οικισμό Αυγής Καστοριάς. ΑΕΜΘ 19, 595-606.

Στρατούλη Γ., 2010. Νεολιθικός Οικισμός Αυγής Kαστοριάς 2006-2007: χωρο-οργανωτικές πρακτικές 6ης και 5ης χιλιετίας. ΑΕΜΘ 21 (2007), 7-14.

Στρατούλη, Γ. & T. Μπεκιάρης. 2011. Αυγή Καστοριάς: στοιχεία της βιογραφίας του νεολιθικού οικισμού. ΑΕΜΘ 22 (2008), 1-10.

Tringham, R., Brukner, B. & Voytek, B. 1985. The Opovo project: a study of socio-economic change in the Balkan Neolithic. Journal of Field Archaeology 12, 425-44.

Tringham, R. & Krstić, D. (eds.). 1990. Selevac: a Neolithic village in

June 2012

Dimitrios Kloukinas